The Land Entitlement Playbook

From Raw Dirt to Buildable Asset: A Complete Guide to Unlocking Value in North & Central Texas

Why This Document Exists

Most landowners and investors understand that raw land has potential. What they often do not understand is how that potential becomes real, legally protected, and financially bankable. The answer is a single word: entitlements.

Land entitlement is the legal and strategic process of securing every government approval, permit, and regulatory clearance necessary to develop a piece of property for a specific use. It is the work that transforms a speculative tract of dirt — one that no bank will lend against and no builder will touch — into a fully approved, shovel-ready asset that commands a premium in the marketplace.

This playbook was written to give you, as a landowner or investor, a clear and honest understanding of that process. It explains what entitlements are, why they matter, how they create value, and exactly what it takes to move a property from unplatted and unentitled through a complete entitlement process in North and Central Texas. Whether your project falls under county jurisdiction, city jurisdiction, or the hybrid authority of an Extraterritorial Jurisdiction (ETJ), this document covers the path.

We wrote this in plain language because the stakes are too high for ambiguity. The entitlement phase is where the most significant value is created in the entire development lifecycle — and it is also where the most money is lost when the process is misunderstood, mismanaged, or skipped entirely.

Downloadable Resource

The H2H Land Entitlement Services Playbook

A comprehensive PDF guide covering H2H's full entitlement service offering — from pre-planning through close-out. Save it, share it with your team, or hand it to your lender.

Download the Playbook (PDF)

The Economics of Entitlement — How Value Is Manufactured

Why Raw Land Is Cheap (And Should Be)

Raw, unentitled land is the riskiest asset class in real estate. It generates no income. It cannot be financed conventionally. And it carries a long list of unanswered questions that make every potential buyer, lender, and builder nervous.

When a builder or investor looks at raw land, they are not evaluating what the land "could be." They are evaluating the cost, time, and risk required to make it something. Every unanswered question suppresses the price they are willing to pay:

Can I legally build what I want here?

If the land is not zoned or platted for the intended use, the buyer absorbs the full risk of navigating the approval process — a process that can take 12 to 24 months, cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and still result in denial.

Are utilities available?

The fact that a water line runs "near" the property means very little. What matters is whether the utility provider has capacity, whether the line is sized to serve the development, what it will cost to extend service, and who pays for it. These answers are often unknown for raw land.

What will the government require me to build?

Counties and cities impose infrastructure requirements — roads, drainage, stormwater systems, fire protection — that can represent 30% to 50% of total development costs. Until those requirements are defined, the financial model is a guess.

How long will this take?

Time is money in development. Every month of delay adds carrying costs (interest, taxes, insurance) and increases exposure to market shifts. Raw land offers no certainty on timeline.

Because of these risks, raw land trades at a steep discount to its potential value. This discount is not a flaw in the market — it is the market correctly pricing uncertainty.

How Entitlements Create Value

The entitlement process systematically eliminates the risks described above. Each approval, each permit, each recorded document removes a layer of uncertainty and replaces it with legal certainty. This de-risking is the mechanism that creates value.

| Stage | Description | Illustrative Value | What Changed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Land | 20 acres, unplatted, no approvals, no utility commitments. | $500,000 | Nothing. Pure speculation. |

| Feasibility Complete | Site confirmed viable: no fatal flaws, utilities available, use permissible. | $600,000 | Risk of a "dead deal" removed. |

| Entitled (Plat Recorded) | Plat approved and recorded, zoning confirmed, utility agreements executed. | $1.2M – $1.5M | Legal right to build secured. Bankable. |

| Permitted & Bonded | All construction permits issued, performance bond posted. | $1.5M – $1.8M | Shovel-ready. Minimal remaining risk. |

| Finished Lots | Roads, utilities, and pads installed. Ready for vertical construction. | $2.5M+ | Builder can start immediately. |

The entitlement phase — the work between "raw land" and "plat recorded" — typically costs approximately 10% to 15% of the land's future entitled value but can generate a 100% to 300% return on the raw land basis. This is the highest-leverage phase in the entire development cycle.

This is the place where you make money in this deal. The entitlement process is where you take a piece of dirt that nobody will lend against and turn it into an asset that generates equity, attracts capital, and gives you leverage.

— Ty Howerton

The Land Residual Model: How Builders Actually Price Land

Understanding how builders value land is essential to understanding why entitlements matter so much. Builders do not use "comparable sales" to price land the way a residential appraiser prices a house. Instead, they use a land residual model, which works backward from the finished product:

Finished Home Value minus All Construction Costs minus Financing Costs minus Builder Profit = Maximum Land Value (Residual)

For example, if a builder can sell a finished home for $450,000, and their all-in costs (construction, fees, financing, profit margin) total $330,000, then the maximum they can pay for a finished lot is $120,000. That is the residual.

The critical insight is this: builders will only pay the full residual value for entitled, finished lots. If the land is not entitled, the builder must discount their offer by the full cost, time, and risk of obtaining entitlements themselves. Most production builders — the national and regional firms that buy lots in volume — will not even consider unentitled land. They want to write a check, pull a permit, and start building.

This means that the entitlement process does not just "add" value. It unlocks the full residual value that was always latent in the land but inaccessible without the legal right to build.

The plat is the legal instrument that creates the right to develop.

The Equity Engine: How Entitlements Finance the Deal

One of the most powerful but least understood aspects of entitlements is their role in project financing. When raw land is worth $500,000 and entitled land is worth $1,500,000, the entitlement process has created $1,000,000 in new equity — on paper, but legally defensible paper.

This equity serves multiple critical functions in the development process:

Performance Bond Collateral.

Counties require developers to post a performance bond equal to 100% of estimated infrastructure construction costs. The increased equity from entitlement can be pledged against these bonds, reducing or eliminating the need for out-of-pocket cash.

Construction Loan Qualification.

Lenders evaluate the loan-to-value ratio of the entitled land when underwriting construction loans. Higher land value means more favorable loan terms, lower equity requirements, and better interest rates.

Investor Attraction.

Entitled land with a clear development plan is a fundamentally different investment proposition than raw dirt. It attracts capital that would never touch an unentitled parcel.

In short, entitlements do not just increase the land's sale price — they create the financial foundation that makes the entire development possible.

The Texas Regulatory Landscape — Who Controls What

Texas has a unique regulatory structure for land development. Unlike many states, Texas counties have very limited authority, while cities have broad powers. Understanding which jurisdiction controls your property is the first and most important step in the entitlement process.

The Three Jurisdictional Zones

Every piece of land in Texas falls into one of three jurisdictional categories, each with a fundamentally different regulatory environment:

| Jurisdiction | Plat Approval | Permits | Zoning | Building Codes | Impact Fees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inside City Limits | City (P&Z + Council) | City | Full zoning power | Yes (IBC/IRC) | Yes |

| Unincorporated County | Commissioners Court | County | None | Limited or none | No |

| City ETJ | City (platting only) | County | None | Limited or none | Varies |

County Development (Chapter 232)

For land in unincorporated areas outside any city's ETJ, the county Commissioners Court is the sole approving authority. Texas counties operate under a fundamentally different philosophy than cities. Their authority is limited and non-discretionary, meaning they can only regulate what state law explicitly authorizes, and if a developer meets the written standards, the county must approve the plat.

What the County Controls:

The county's review is focused on ensuring that the proposed subdivision meets minimum standards for public health, safety, and infrastructure. This includes road design and construction standards (width, materials, drainage), water supply adequacy, wastewater treatment (typically on-site sewage facilities in rural areas), drainage and floodplain compliance, and the posting of a performance bond to guarantee infrastructure completion.

What the County Cannot Do:

A Texas county cannot zone land. It cannot dictate whether a property is used for residential, commercial, or industrial purposes. It cannot impose architectural standards, density limits, or design requirements beyond what is explicitly authorized by state statute. Recent legislation (HB 3697, effective September 2023) further restricted county authority by prohibiting counties from requiring any "analysis, study, document, agreement, or similar requirement" that is not explicitly required by state law.

The County Approval Process:

The typical county platting process follows a structured sequence. The developer submits a plat application with required engineering documents to the county. County staff reviews the submission for compliance with subdivision regulations. A comment period allows staff to request revisions or additional information. The developer responds to comments and resubmits if necessary. The final plat is presented to the Commissioners Court for approval. Upon approval, the plat is recorded with the county clerk, creating a legal subdivision.

State law requires the county to act on a plat application within 30 days of a complete submission, with specific procedures for conditional approval, disapproval, and resubmission.

City Development (Chapter 212)

Developing within a city's corporate limits is a fundamentally different experience. Cities in Texas have the full range of land-use regulatory tools, and the process is both more complex and more discretionary.

Zoning: The Gatekeeper.

Every city with a zoning ordinance assigns a zoning classification to each parcel of land. This classification dictates what can be built (use), how much can be built (density/intensity), and how it must be configured (setbacks, height, lot coverage). If the proposed project does not conform to the existing zoning, the developer must apply for a rezoning — a discretionary process that requires public notice, a public hearing before the Planning & Zoning Commission, and a vote by the City Council. Rezoning is never guaranteed and is often the most politically sensitive step in the entire process.

Site Plan Review.

Beyond the plat, cities require a detailed site plan that shows the precise layout of buildings, parking, landscaping, signage, lighting, and other features. This plan is reviewed by multiple city departments (planning, engineering, fire, utilities, parks) for compliance with a comprehensive set of development standards.

Impact Fees.

Texas cities are authorized to charge impact fees to offset the cost of new infrastructure (water, sewer, roads, parks) demanded by new development. These fees can be substantial — often $5,000 to $15,000 or more per residential unit — and must be factored into the project's financial model.

Building Codes.

Cities enforce the International Building Code (IBC) and International Residential Code (IRC), which govern the design and construction of all structures. This adds another layer of review and permitting beyond the land entitlement process.

The ETJ: Navigating Dual Jurisdiction

The Extraterritorial Jurisdiction (ETJ) is the area outside a city's corporate limits where the city has been granted limited regulatory authority by state law. The size of the ETJ depends on the city's population, ranging from one-half mile for cities under 5,000 to five miles for cities over 100,000.

In the ETJ, a split authority model exists. The city controls the subdivision platting process, applying its own subdivision ordinance to regulate the design of streets, lots, blocks, drainage, and other infrastructure. However, the city cannot impose zoning in the ETJ. The county retains authority over development permits, on-site sewage facilities, and other regulatory functions.

This dual jurisdiction creates unique challenges. The city's subdivision standards may require wider roads, more extensive drainage systems, or different utility configurations than the county would require on its own. The developer must navigate both sets of requirements simultaneously, and the two jurisdictions do not always coordinate seamlessly.

For projects in the ETJ, the entitlement strategy must account for both the city's platting requirements and the county's permitting requirements from the outset. Failure to do so can result in costly redesigns, delays, and conflicts between the two jurisdictions.

SB 840 & the Shift Toward By-Right Development

Texas Senate Bill 840 (SB 840), which became effective on September 1, 2025, represents one of the most significant changes to Texas land-use law in decades. The law applies to municipalities with populations over 150,000 that are wholly or partly in counties with more than 300,000 residents — including Dallas, Fort Worth, Arlington, Plano, Frisco, Austin, Round Rock, and Houston.

SB 840 requires these cities to allow multifamily and mixed-use residential projects by right — without rezoning, variances, or other discretionary approvals — in any zoning district that permits office, commercial, retail, or warehouse uses. Key provisions include:

| Provision | Requirement |

|---|---|

| Minimum Density | 36 units per acre |

| Minimum Height | 45 feet |

| Maximum Parking | 1 space per unit |

| Approval Type | Administrative (non-discretionary) |

For developers and landowners, SB 840 fundamentally changes the entitlement calculus for multifamily projects in major Texas cities. Land that was previously zoned for commercial or office use — and would have required a lengthy, uncertain rezoning process for residential development — can now be developed for multifamily housing through an administrative process. This dramatically reduces entitlement risk and timeline for qualifying projects, and it has already begun to reshape land values in affected areas.

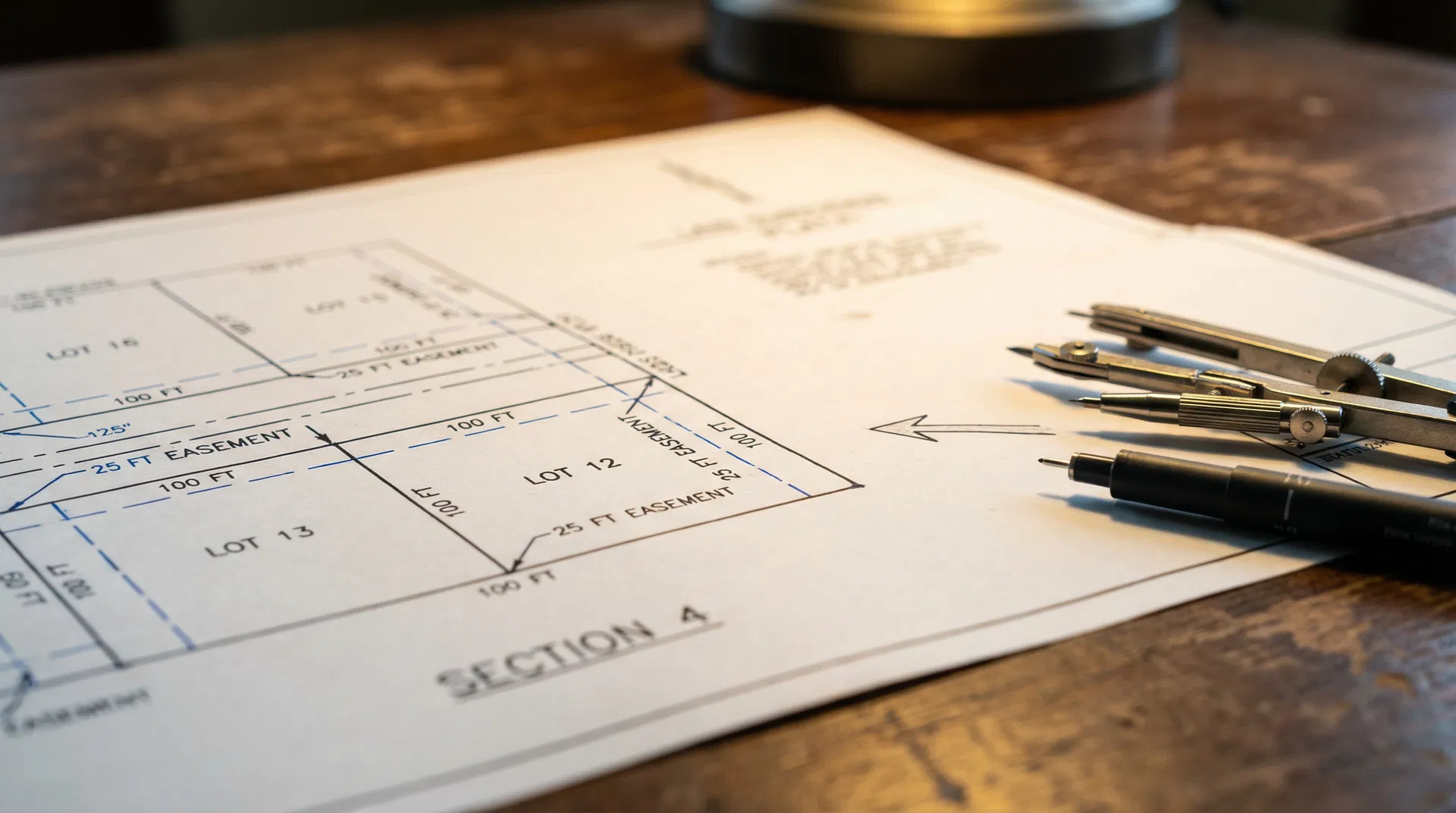

Survey stakes mark the beginning of the entitlement journey — raw land waiting to be transformed.

The H2H Entitlement Process — A Phased Approach to Certainty

The following framework represents our proven, battle-tested approach to moving a project from raw land to a fully entitled, shovel-ready asset. It is organized into six sequential phases, each with clear objectives, deliverables, and decision points.

Pre-Planning — The 'Go/No-Go' Decision

Determine whether the project is viable before significant capital is committed.

This is the most important phase in the entire process. Every dollar spent here saves ten dollars later. We conduct a comprehensive investigation of the property and its regulatory environment to identify fatal flaws, quantify risks, and develop a realistic development strategy.

Project Kick-Off & Feasibility Review.

We begin with a thorough review of the property's physical characteristics, legal status, and regulatory context. This includes confirming ownership and title, reviewing existing surveys and legal descriptions, identifying all governing jurisdictions, and researching any pending or adopted plans that could affect the property.

Land Survey & Site Data Collection.

A current boundary and topographic survey is essential. We also collect data on soils, vegetation, existing improvements, and adjacent land uses. For properties in or near floodplains, we obtain the most current FEMA flood maps and, if necessary, commission a detailed flood study.

Environmental & Floodplain Assessment.

We evaluate the property for environmental constraints including wetlands, endangered species habitat, contamination, and cultural resources. Floodplain status is confirmed and, where applicable, we assess the feasibility and cost of floodplain mitigation or avoidance.

Utility Service Feasibility.

This is not a cursory check. We trace the nearest water, sewer, electrical, gas, and telecommunications lines to the property. We contact each utility provider to confirm capacity, connection requirements, and costs. We identify whether the property can be served by existing infrastructure or whether extensions, upgrades, or new facilities are required.

Preliminary Site Plan Layout.

Based on the data collected, we develop a preliminary conceptual layout that tests the property's development potential. This layout is not a final design — it is a tool for evaluating density, circulation, open space, and infrastructure requirements.

Deliverable

A comprehensive Feasibility Report with a clear "go/no-go" recommendation.

Platting — Securing the Legal Foundation

Prepare and secure approval of the subdivision plat — the legal document that creates the right to develop.

The plat is the cornerstone of the entitlement process. It is the legal instrument that divides the land into lots, blocks, and public dedications (roads, drainage easements, utility easements) and establishes the framework for all subsequent development.

Engineering Design & Infrastructure Development.

Civil engineers prepare detailed construction plans for all required infrastructure, including grading and earthwork plans, stormwater drainage design, road and paving plans, water distribution and wastewater collection systems, erosion control plans, and utility coordination plans.

Owner's Certificate & Document Preparation.

The plat must include an owner's certificate — a legal document signed by the property owner that dedicates public rights-of-way and easements and certifies the accuracy of the plat. We prepare all required supporting documents, including the plat itself, the owner's certificate, a title commitment, and any required fiscal security.

Plat Submission, Review & Approval.

The complete application package is submitted to the appropriate authority. Government staff reviews the submission for compliance. Comments are issued and addressed. The final plat is presented for a vote and, upon approval, recorded with the county clerk — the moment the land becomes a legal subdivision.

Permitting — Clearing the Final Regulatory Hurdles

Secure all construction and development permits required to begin building.

With the plat recorded, the land is legally entitled. However, construction cannot begin until a series of specific permits are obtained:

| Permit | Issuing Authority | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Development Permit | County | Authorizes site development and construction activity. |

| OSSF Permit | County (delegated by TCEQ) | Authorizes on-site sewage facilities (septic systems). |

| TCEQ Stormwater (SWPPP) | TCEQ | Required for sites disturbing 1+ acres. |

| Floodplain Development | County or City | Required for development within FEMA floodplains. |

| Driveway / Entrance | County or TxDOT | Authorizes access points to public roads. |

| 911 Addressing | County | Assigns official addresses and road names. |

Utility Coordination — Connecting to the Grid

Secure binding agreements with all utility providers and coordinate service installation.

Utility coordination is one of the most underestimated aspects of the development process. "Utilities are available" is one of the most dangerous phrases in real estate — it often means nothing more than "there is a line somewhere in the general vicinity."

Our utility coordination process includes securing a formal water supply arrangement with the applicable water district, municipality, or co-op; coordinating electrical service including transformer sizing, meter placement, and any required line extensions; arranging telecommunications and internet service; and conducting a utility pre-construction meeting with all providers to confirm schedules, access requirements, and construction sequencing.

Construction — Building the Horizontal Infrastructure

Install all required infrastructure to create finished, buildable lots.

With all permits and utility agreements in place, construction begins. This phase transforms the entitled land into finished lots. The typical construction sequence includes erosion control installation and site clearing, rough grading and earthwork, underground utility installation, road and pad construction, building construction (if applicable), power, water, and utility connections, and landscaping and site finishes.

Throughout construction, we coordinate inspections with the county or city, manage the SWPPP compliance requirements, and ensure that all work meets the approved plans and specifications.

Close-Out — Final Inspections and Project Completion

Secure final approvals, release bonds, and deliver the completed project.

The final phase involves completing all required inspections, obtaining final sign-offs from the county or city, filing the SWPPP Notice of Termination with TCEQ, and initiating the process to release or reduce the performance bond.

For county projects in unincorporated areas, there is typically no formal "Certificate of Occupancy." Instead, the final county inspection serves as confirmation that the development has been completed in accordance with the approved plans.

The Value Chain — What Each Phase Is Worth

Understanding where value is created allows you to make smarter decisions about when to invest, when to hold, and when to sell. The following table summarizes the value creation at each phase of the process:

| Phase | Investment | Value Created | Risk | Exit Option |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Land Acquisition | Land cost only | Baseline (1x) | Highest | Sell as raw land (deep discount). |

| Feasibility Complete | + $25K – $75K | 1.1x – 1.2x | High | Sell with feasibility package. |

| Plat Recorded (Entitled) | + $150K – $500K | 2x – 3x | Moderate | Sell entitled land to builder. |

| Permitted & Bonded | + $50K – $150K | 2.5x – 3.5x | Low-Moderate | Sell shovel-ready project. |

| Finished Lots | + $500K – $2M+ | 4x – 6x+ | Low | Sell finished lots to builders. |

The most important takeaway from this table is that the entitlement phase (feasibility through plat recording) represents the highest return on invested capital in the entire process. The investment is relatively modest compared to the construction phase, but the value creation is dramatic. This is the phase where strategic, knowledgeable execution generates the greatest financial leverage.

The Density Unlock — How Package Wastewater Plants Transform Land Value

Everything in this playbook leads to one question: how many units can you put on the land? Density is the multiplier that determines whether a 30-acre tract is worth $1.5 million or $12 million. And in county and ETJ development across North and Central Texas — where municipal sewer lines often stop miles short of the site — the single biggest constraint on density is wastewater disposal.

If you are building on septic systems, the State of Texas dictates your lot sizes. Half-acre minimum with public water. One-acre minimum with a well. That is not a suggestion — it is codified in 30 TAC §285.4, and there is no variance process. Your density is capped before you ever draw a site plan.

A package wastewater treatment plant removes that cap. It provides centralized sewer service to the development, which means the minimum lot size requirements under Chapter 285 no longer apply. Your density is now governed by the plat, the jurisdiction's development standards, and the capacity of the plant — not by a septic regulation written for rural homesteads.

The Septic Ceiling: 30 TAC §285.4

TCEQ regulates on-site sewage facilities (OSSFs) — commonly known as septic systems — under 30 TAC Chapter 285. Section 285.4 establishes minimum lot sizes for any subdivision that relies on individual septic systems for wastewater disposal.

| Wastewater Method | Water Source | Minimum Lot Size | Authority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Septic (OSSF) | Public Water Supply | 0.50 acres (21,780 sf) | 30 TAC §285.4(a)(1)(A) |

| Individual Septic (OSSF) | Private Well | 1.00 acres (43,560 sf) | 30 TAC §285.4(a)(1)(B) |

| Centralized Sewer (Package Plant) | Public Water Supply | No TCEQ minimum | Chapter 217 / Permit |

| Centralized Sewer (Package Plant) | Private Well + Package Plant | No TCEQ minimum | Chapter 217 / Permit |

This table is the entire argument in four rows. When you build on septic, the state tells you how many lots you can have. When you build with centralized sewer — even a private package plant — the state steps back and lets the development plan dictate density.

A package plant is a pre-engineered, pre-fabricated treatment facility that processes domestic sewage to a quality standard that meets TCEQ discharge or land-application requirements. Modern systems are engineered steel or concrete with 20- to 30-year service lives, equipped with SCADA monitoring, automated controls, and the same treatment processes used in municipal facilities.

Package plants range in capacity from approximately 10,000 gallons per day (GPD) — enough for roughly 30 homes — to over 1,000,000 GPD, which can serve master-planned communities of several thousand units. They can be installed in phases, starting with the capacity needed for the first section and expanding as additional phases come online.

TCEQ Permit Types: TPDES vs. TLAP

Every package plant in Texas requires a TCEQ permit. The permit type depends on how the treated effluent is disposed of.

TPDES (Texas Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permits authorize the discharge of treated effluent into "waters of the state" — a creek, stream, or river. TPDES permits carry more stringent effluent quality limits, require a regionalization analysis (demonstrating that connecting to an existing municipal system is not feasible), and involve a public notice and comment period.

TLAP (Texas Land Application Permit) permits authorize the disposal of treated effluent through land application — surface irrigation, subsurface drip irrigation (SDI), evaporation, or drainfields. No treated water enters surface waters. TLAP permits do not require a regionalization analysis, which significantly simplifies the permitting process.

| Factor | TPDES Permit | TLAP Permit |

|---|---|---|

| Effluent Disposal | Discharge to surface water | Land application (irrigation, SDI, drainfields) |

| Regionalization Analysis | Required | Not required |

| Effluent Quality Standards | More stringent (BOD, TSS, ammonia) | Standard treatment quality |

| Public Notice/Comment | Required | Required (simpler process) |

| Best For | Sites near creeks/streams | Sites with open space — most county/ETJ developments |

| Developer Preference | Less common for private development | Strongly preferred — avoids discharge issues |

For most county and ETJ developments in North Texas, the TLAP route is strongly preferred. Subsurface drip irrigation turns wastewater disposal into an irrigation system that reduces the development's potable water demand. Under 30 TAC Chapter 210, treated effluent can be classified as reclaimed water and reused for landscape irrigation, common area irrigation, and other beneficial purposes.

The Density Math — What a Package Plant Is Actually Worth

The following analysis uses a 30-acre tract in a North Texas county or ETJ — a common development scenario in Rockwall, Kaufman, Collin, and Denton counties. We assume 80% net developable area after deducting roads, drainage, open space, and setbacks (24 net acres).

Scenario A: Septic + Public Water

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Gross Acreage | 30 acres |

| Net Developable | 24 acres (80%) |

| Minimum Lot Size | 0.50 acres |

| Maximum Lot Yield | 48 lots |

| Estimated Lot Value | $150,000 |

| Gross Lot Revenue | $7,200,000 |

Scenario B: Septic + Private Well

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Gross Acreage | 30 acres |

| Net Developable | 24 acres (80%) |

| Minimum Lot Size | 1.00 acres |

| Maximum Lot Yield | 24 lots |

| Estimated Lot Value | $200,000 |

| Gross Lot Revenue | $4,800,000 |

Scenario C: Package Plant — Standard Residential

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Gross Acreage | 30 acres |

| Net Developable | 24 acres (80%) |

| Average Lot Size | 8,500 sf (~0.20 acres) |

| Maximum Lot Yield | ~120 lots |

| Estimated Lot Value | $100,000 |

| Package Plant Cost | $800,000 – $1,200,000 (40,000 GPD) |

| Gross Lot Revenue | $12,000,000 |

Scenario D: Package Plant — Higher Density (Townhomes / Small Lot)

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Gross Acreage | 30 acres |

| Net Developable | 24 acres (80%) |

| Average Unit Size | 4,000 sf (~0.09 acres) |

| Maximum Unit Yield | ~200 units |

| Estimated Unit Value | $80,000 |

| Package Plant Cost | $1,200,000 – $2,000,000 (75,000 GPD) |

| Gross Unit Revenue | $16,000,000 |

The Value Delta: An investment of $800,000 to $2,000,000 in a package plant unlocks $3.6 million to $7.6 million in additional gross revenue compared to the septic baseline. That is a 3x to 5x return on the infrastructure investment — before a single vertical stick of framing goes up.

| Scenario | Lot/Unit Yield | Gross Revenue | Infrastructure Cost | Net Value vs. Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Septic + Public Water | 48 lots | $7,200,000 | Minimal | Baseline |

| B: Septic + Well | 24 lots | $4,800,000 | Minimal | ($2,400,000) |

| C: Package Plant — Standard | 120 lots | $12,000,000 | $800K – $1.2M | +$3,600,000 to +$4,000,000 |

| D: Package Plant — High Density | 200 units | $16,000,000 | $1.2M – $2.0M | +$6,800,000 to +$7,600,000 |

This is why package plants are not a cost. They are a value creation instrument.

How a Single Plant Serves Multiple Tracts

One of the most common questions developers ask: "If I subdivide my 30 acres into five tracts and sell them to different builders, how does one package plant serve the whole development?" The answer is straightforward, and it is done routinely across Texas.

Step 1: Master Plan the Entire Tract

Before any subdivision occurs, the developer creates a master utility plan that identifies the package plant location, the collection system routing (gravity sewer mains, force mains, and lift stations if needed), and the effluent disposal area. This plan is engineered to serve the full buildout of all tracts.

Step 2: Plat with Utility Easements

When the 30 acres is platted into five tracts, the plat includes recorded utility easements across every tract for the sewer collection system. These easements are permanent and run with the land — they survive any future sale or transfer of individual tracts.

Step 3: Site the Plant on a Dedicated Utility Tract

The package plant is typically located on a small dedicated tract (often 0.25 to 0.50 acres) or within a common-area parcel. This tract is owned by the entity that will operate the plant — the HOA, a property owners' association (POA), a special district, or a third-party operator.

Step 4: Obtain a Single TCEQ Permit

The TCEQ permit covers the entire service area — all five tracts. The permit is issued to the entity that owns and operates the plant, not to the individual tract owners. The permit specifies the plant's capacity, effluent quality limits, monitoring requirements, and disposal method.

Step 5: Connect Each Tract as It Develops

As individual tracts are sold to builders and developed, each tract connects to the shared collection system. The package plant can be installed in phases — initial capacity for the first one or two tracts, with modular expansion as additional tracts come online.

Step 6: Fund Through Utility Fees or Assessments

Each lot or unit within the development pays a monthly utility fee for wastewater service, just as they would pay a municipal sewer bill. These fees fund the ongoing operation, maintenance, and eventual replacement of the plant.

Ownership & Operation Models

| Model | How It Works | Developer Liability | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOA/POA Ownership | Developer builds plant, transfers to HOA at buildout. HOA contracts with licensed operator. | Ends at transfer | Smaller developments (50–150 units) |

| Special District (MUD/FWSD) | Developer petitions to create a district. District issues bonds, builds, and operates. | Ends when district assumes ops | Larger developments (200+ units), bond financing |

| Build-Own-Operate (BOO) | Third-party company designs, builds, owns, and operates under long-term contract. | Minimal — contractual only | Developers wanting zero operational risk |

| Lease Model | Developer leases modular plant. Scaled up/down as demand changes. Purchase option at buildout. | Limited to lease terms | Phased developments with uncertain absorption |

For most county and ETJ developments in North Texas, the HOA/POA model or the special district model are the most common paths. The BOO and lease models are gaining traction rapidly because they shift operational risk entirely off the developer's balance sheet.

The Permitting Pathway — Timeline and Process

| Phase | Duration | Key Deliverables |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Application | Months 1–3 | Site assessment, flow calculations, regionalization analysis (TPDES only), pre-application conference |

| Application Preparation | Months 3–6 | Engineering design (Ch. 217), collection system design, effluent disposal plan, Public Involvement Plan, SB 1586 compliance |

| Agency Review | Months 6–14 | TCEQ technical review, RAI responses, public notice and comment period |

| Permit Issuance + Construction | Months 14–18 | Permit issued, plant fabrication, installation, commissioning, startup testing |

Texas law requires that applications be submitted a minimum of 330 days before the planned operation date. This timeline runs concurrently with the entitlement process described earlier in this playbook. A well-coordinated project will have the TCEQ permit application submitted during the platting phase, so that the permit is issued around the same time the plat is recorded and construction permits are pulled.

Under SB 1586 (effective September 1, 2025), the application must demonstrate that the proposed package plant is not located within 1,000 feet of an existing municipal wastewater line. This is a hard prohibition — if a municipal line is within 1,000 feet, TCEQ cannot issue the permit.

2025 Legislation: SB 1586 & SB 7

SB 1586 (Senator Charles Schwertner, effective September 1, 2025) adds two significant requirements. First, the 1,000-foot proximity prohibition — TCEQ cannot issue a permit for a package plant within 1,000 feet of an existing municipal wastewater line. Second, applicants must demonstrate financial assurance and weatherization measures adequate to fund future maintenance. For responsible developers, this formalizes what good practice already demands.

SB 7 (signed June 2025) creates the $22.5 billion Texas Water Fund — the largest water infrastructure investment in Texas history, administered by the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). Developers can access it through eligible political subdivisions (MUDs, FWSDs, WCIDs). Rural projects serving populations under 10,000 may qualify for up to 100% loan forgiveness. Critically, water reuse systems qualify as "new water supply" projects — meaning a package plant with a TLAP permit and subsurface drip irrigation could be eligible for state funding.

For a developer structuring a project through a MUD or FWSD, SB 7 fundamentally changes the economics of package plant infrastructure. Instead of funding the plant entirely through private capital, the district can access low-interest state loans — or in some cases, grants — that reduce the developer's out-of-pocket cost and accelerate the project timeline.

The 30-Acre, Five-Tract Development — A Working Example

A 30-acre tract in the ETJ of a North Texas city. The nearest municipal sewer line is 2.3 miles away. Public water is available via a water supply corporation (WSC) with a 6-inch main along the frontage road. The developer intends to subdivide the tract into five development parcels and sell finished lots to three different builders.

Phased Development Plan

| Phase | Tracts Developed | Lots Delivered | Plant Capacity Online | Cumulative Investment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Tracts 1 and 2 | 50 lots | 25,000 GPD | $650,000 |

| Phase 2 | Tract 3 | 35 lots | 50,000 GPD (expansion) | $350,000 |

| Phase 3 | Tracts 4 and 5 | 55 lots | 75,000 GPD (full capacity) | $400,000 |

| Total | All 5 Tracts | 140 lots | 75,000 GPD | $1,400,000 |

Project Economics

| Line Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Raw Land Value (30 acres, unentitled) | $900,000 |

| Entitlement Cost (H2H fees, engineering, permits) | $450,000 |

| Package Plant + Collection System (all phases) | $1,400,000 |

| Total Investment | $2,750,000 |

| Finished Lot Value (140 lots × $95,000 avg.) | $13,300,000 |

| Gross Margin | $10,550,000 |

Compare this to the same 30 acres developed on septic with public water: 48 lots at $150,000 = $7,200,000 gross revenue, with a gross margin of approximately $5,500,000. The package plant route nearly doubles the gross margin while creating a more marketable, higher-density product that builders prefer.

The $1.4 million package plant investment generated approximately $5 million in additional margin. That is a 3.5x return on the infrastructure spend alone. The question is not whether a package plant makes sense. The question is whether you can afford to leave that density — and that value — on the table.

Before engineering, before design, before capital deployment — clarity matters. Schedule a strategic planning session to pressure-test your project's viability, entitlement pathway, and long-term positioning. Smart development begins with disciplined evaluation.

Schedule a Strategic Planning Session

Certainty Is the Product We Deliver

The land entitlement process is not paperwork. It is not bureaucracy. It is the deliberate, strategic conversion of uncertainty into certainty — and certainty is the most valuable commodity in real estate development.

When we complete the entitlement process for your property, we have answered every question that suppresses land value. We have secured the legal right to build. We have confirmed utility service. We have defined the infrastructure requirements and their costs. We have navigated the political and regulatory landscape. And we have created a bankable, marketable, financeable asset where there was once only dirt and speculation.

That is what entitlements do. That is the value they unlock. And that is what the H2H Design Group delivers.

H2H Design Group

House 2 Home Plans · H2H Commercial Plans · H2H Planning